Full-service community hospitals, policymakers, the business community and governmental advisory bodies have long grappled with the shortcomings, including overutilization and higher health care costs, caused by self-referrals to physician-owned hospitals. Conflicts of interest are inherent in these arrangements, where physicians refer their patients to hospitals in which they have an ownership interest. Thirteen years ago, after a decade of studies and Congressional hearings showing the adverse impact of these arrangements, Congress acted to protect the Medicare and Medicaid programs, and the taxpayers that fund them, by imposing a prospective ban on self-referral to physician-owned hospitals (POH).

Nevertheless, groups like the trade association representing POHs continue to attempt to unwind the law. This would harm patients, full-service community hospitals, and local businesses. Proponents of weakening the law are now arguing that the underlying data that fueled congressional action is out-of-date and current data no longer supports the earlier findings.

A new study conducted by the health care economics consulting firm Dobson | DaVanzo refutes that argument and presents new findings that reinforce the reasons why Congress acted.

What the Data Show

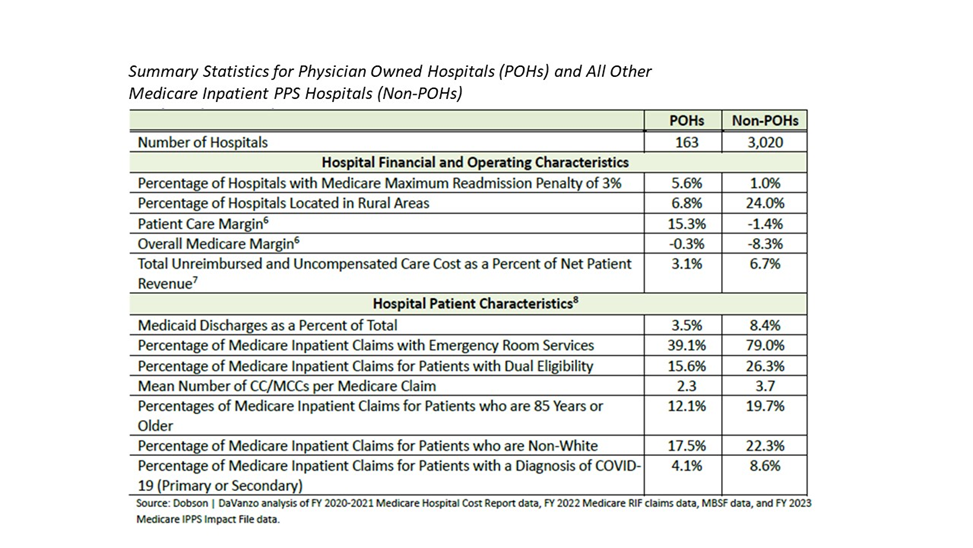

The Dobson | DaVanzo analysis compares the performance of non-physician owned, full-service community hospitals with physician-owned hospitals It provides a clear picture that the characteristics of these POHs virtually mirror the findings and data collected in the early-to-mid 2000’s that drove Congress to enact the law prospectively banning self-referral to these facilities. Among those findings, physician-owned hospitals:

- cherry pick patients by avoiding Medicaid and uninsured patients;

- treat fewer medically complex patients; and

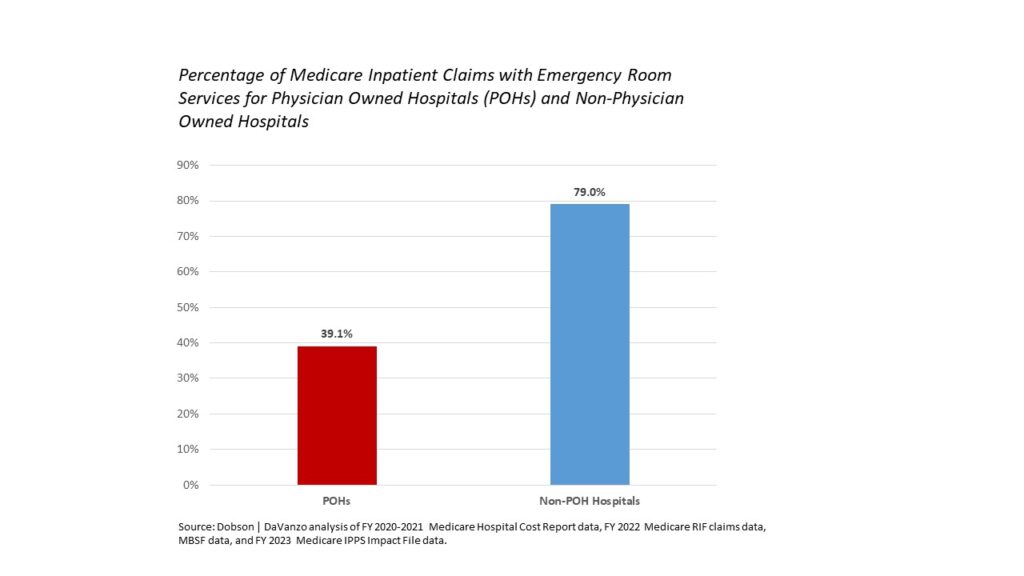

- provide few emergency services, an important community benefit.

The Dobson | Davanzo study not only reaffirms those findings but also reports that POHs:

- enjoy patient care margins more than 15 times that of other hospitals;

- are 5 times more likely to be assessed the maximum penalty for readmissions; and

- have less than half the rate of COVID-19 patients.

Physician-owned hospitals still cherry pick –avoiding Medicaid, uninsured and medically complex patients.

Physician-owner referrals result in the “cherry picking” of patients. Analyses previously conducted by both GAO and MedPAC clearly found that physician owned specialty hospitals avoided lower-income or non-paying patients.

“Specialty hospitals uniformly denied selecting cases based on payer mix but the specialty hospitals we visited had much lower Medicaid shares and provided less uncompensated care. One physician told us the specialty hospital had used the lack of uninsured patients as a marketing pitch to him.” (MedPAC staff, transcript, pg. 179, September 2004)

“Relative to general hospitals in the same urban areas, specialty hospitals in our HCUP sample tended to treat a lower percentage of Medicaid inpatients among all patients with the same types of conditions.” (GAO-04-167 (October 22, 2003), pg. 20, “Specialty Hospitals: Geographic Location, Services Provided, and Financial Performance.)

“…physician-owned specialty hospitals tend to have lower Medicaid shares than both community hospitals in their market and peer hospitals that provide similar services….These findings are consistent with earlier work by the GAO and consistent with what we found on site visits to communities with physician-owned hospitals.” (MedPAC staff, transcript, pg. 174, September 2004)

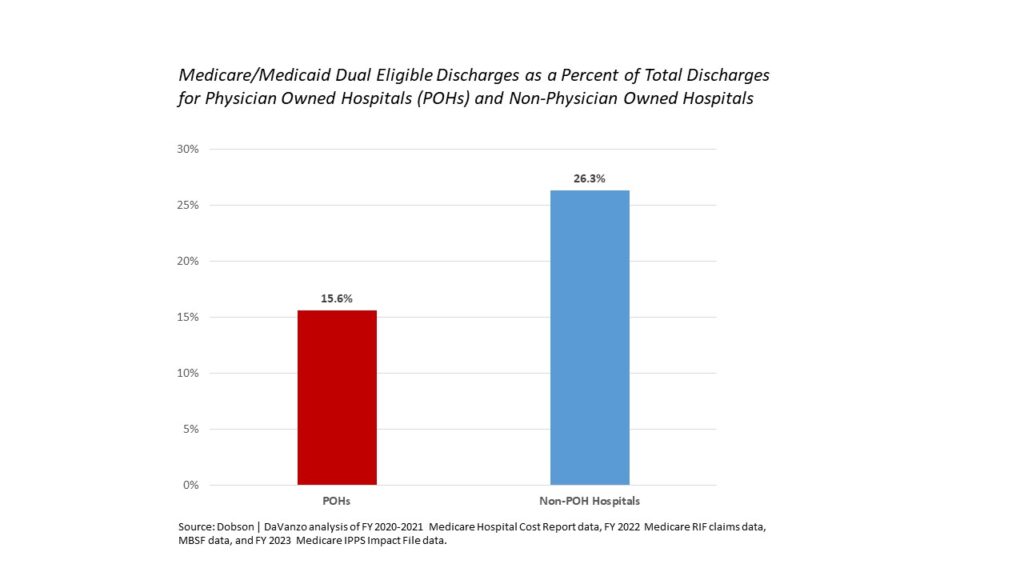

Using the most recent data available, the Dobson | DaVanzo analysis shows once again that POHs have proportionately far fewer Medicaid discharges, dual eligible (Medicaid and Medicare) patients and uncompensated care costs.

A key characteristic of cherry picking is avoiding patients that may have higher complexity or comorbidity. Under the Medicare hospital payment system, CMS has identified those diagnoses whose presence as a secondary diagnosis leads to substantially increased hospital resource use, or cost. Referred to as complication or comorbidity (CC) or a major complication or comorbidity (MCC), the higher the CC or MCC count, the higher the likelihood of greater costs borne by the hospital.

According to the Dobson | DaVanzo analysis, non-physician owned hospitals have a significantly higher number of CC/MCCs per Medicare claim as POHs.

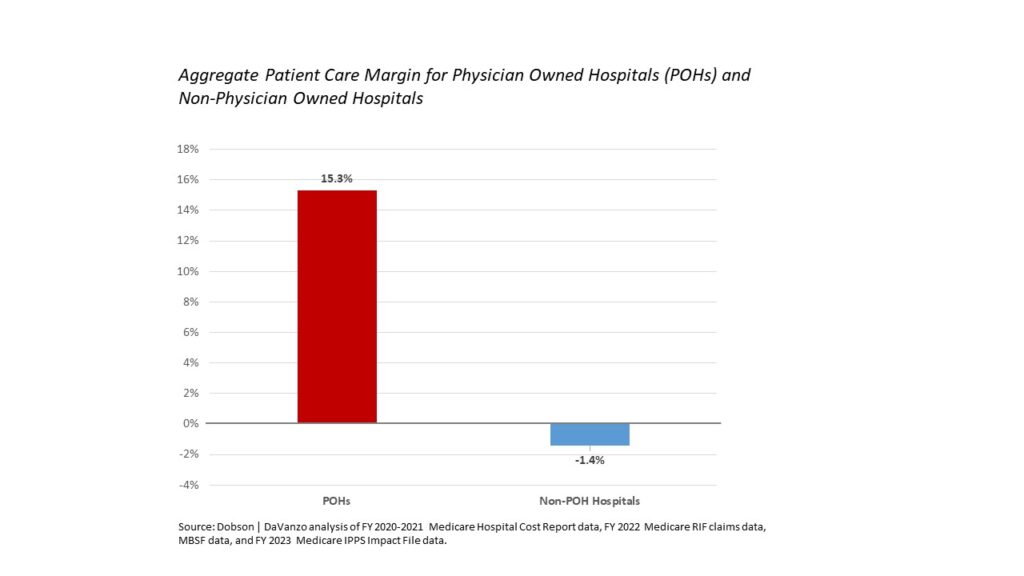

This “cherry picking” – avoiding Medicaid, dual eligible, and uninsured patients, and treating low-cost, low complexity patients – creates an unlevel playing field that enables physician-owned hospitals to enjoy patient care margins more than 15 times the patient care margin of non-physician-owned community hospitals, according to data from Dobson | DaVanzo.

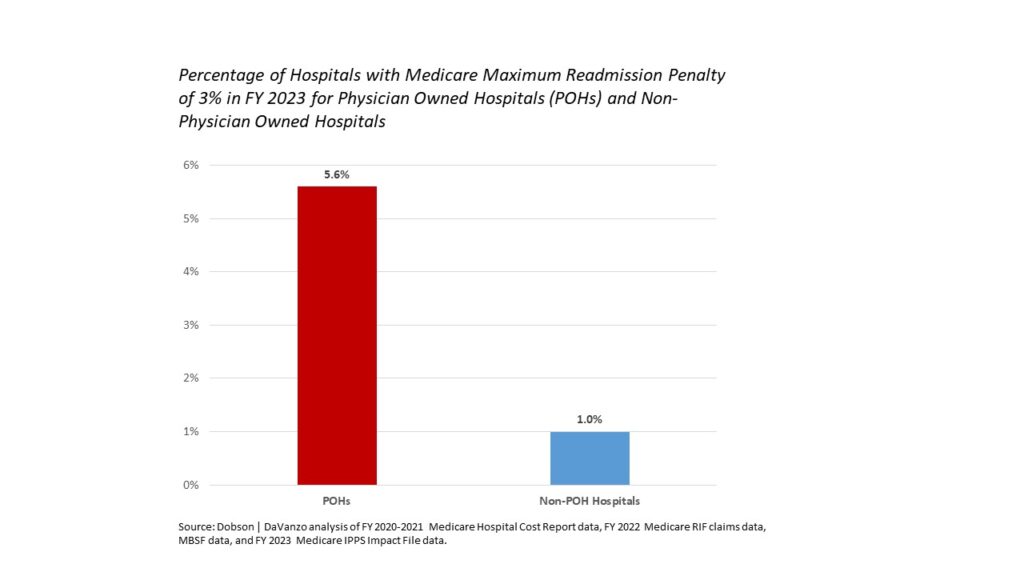

Readmission rates are considered an important barometer of a hospital’s quality of care and in 2010 Congress created a readmissions payment penalty program with a maximum penalty of three percent. Since that time, there has been a significant drop in the overall readmissions rate among all hospitals. Yet even with lower complexity patients on average, the Dobson | DaVanzo study finds that POHs were more than five times more likely to be assessed the maximum readmissions penalty.

Emergency Services Appear to be Lacking in Physician-Owned Hospitals

A key measure of whether a hospital is providing a community benefit is the presence of emergency and trauma services. The lack of emergency services provided in physician-owned hospitals is well documented.

In 2003, GAO found that “The emergency departments at specialty hospitals treated less than one-tenth the median number of patients treated at the emergency departments of general hospitals.” (GAO-04-167 (October 22, 2003), pg.18, “Specialty Hospitals: Geographic Location, Services Provided, and Financial Performance.)

And in September 2004, MedPAC staff reported that “many of the specialty hospitals we visited did not have emergency rooms, which increases their control over admissions. But even having an emergency room didn’t mean the hospital was ready to treat emergencies. At one hospital we visited, it had to turn on the lights of its emergency room to show us the space.”

Further, in 2008, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Inspector General (HHS OIG) issued a report regarding the ability of physician-owned specialty hospitals to respond to and manage medical emergencies. The HHS OIG report found, in part, that “[t]wo-thirds of physician-owned specialty hospitals use 9-1-1 as part of their emergency response procedures,” and “[m]ost notably, 34 percent of [specialty] hospitals use 9-1-1 to obtain medical assistance to stabilize patients, a practice that may violate Medicare requirements.”

The most recent data from Dobson | DaVanzo indicates that little has changed.

Conclusion: Data Continues to Strongly Support Need to Maintain Current Law

There is a substantial history of Congressional policy development and underlying research on the impact of self-referral to physician-owned hospitals. The empirical record is clear that these conflict-of-interest arrangements of hospital ownership and self-referral by physicians results in cherry picking the healthiest and wealthiest patients, excessive utilization of care and patient safety concerns. This policy development includes more than a decade of work by Congress, involving numerous hearings, as well as analyses by the HHS Office of Inspector General (OIG), Government Accountability Office (GAO) and Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). And now, using the most recent data publicly available, Dobson | DaVanzo has reaffirmed much of that work, and added new data-based reasons to retain the current law.

In short, the dangers of self-referral remain, and the foundation for current law must not be weakened. Congressional Budget Office scoring of proposals over the years to modify existing law consistently demonstrate that self-referral to physician owned hospitals increases utilization, which increases Medicare costs and health care costs generally. This is a key reason why the U.S. Chamber of Commerce has long supported the ban on self-referral to physician-owned hospitals.

The law enacted in 2010 is working exactly as planned to ensure a more level playing field – one that promotes fair competition. It is a carefully crafted policy with an important safeguard that permits limited expansion of grandfathered hospitals to meet demonstrated community need, though we do note our concern with the recent weakening of a key regulatory criterion that undermines Congressional intent. Several physician-owned hospitals, in fact, have met the requirements. The law works and it must be maintained.

The complete report can be found here.